Story Content

Batting for the underdog: Sac State researcher champions misunderstood flying mammals

March 25, 2025

Bats are not scary, creepy or blood thirsty.

In truth, says Sacramento State Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences Anna Doty, they are fascinating, valuable and resourceful creatures. Some of them are even cute.

“I will take any opportunity I get to talk about bats or dispel myths about them,” said Doty, who uses her animal physiology background to research how bats interact with their environments. “They are truly incredible.”

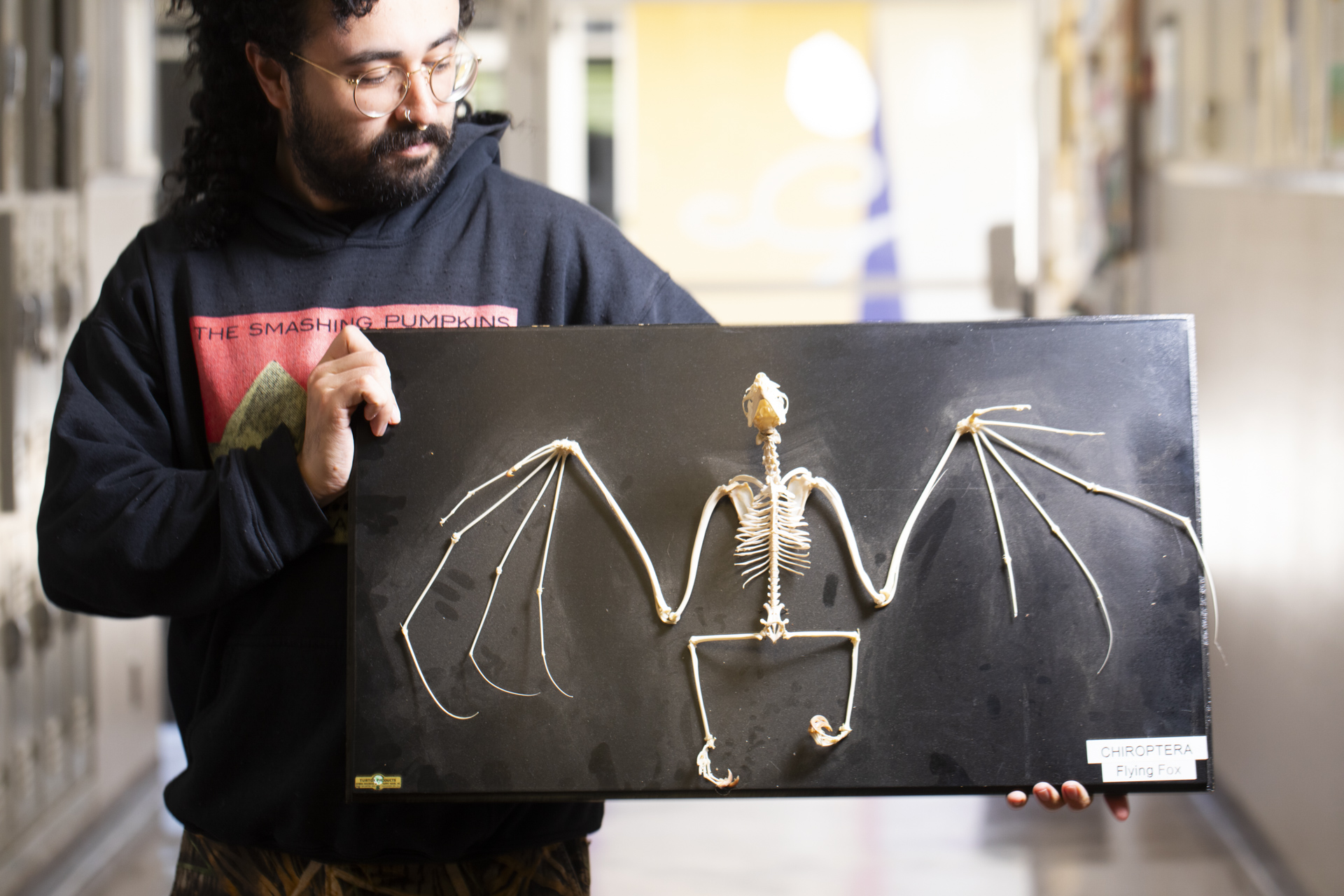

Doty and her students study the many ways bats interact with their environments and how issues such as climate change and wildfires affect their populations and habits. They work both on campus, where they have access to preserved bat specimens, and in the field in places like Sequoia National Forest.

“I have been in caves with thousands of bats, and never once has one come at me. Bats have no interest in being around humans.” -- Anna Doty, assistant professor of Biological Sciences

The researchers capture bats in fine mesh “mist nets” and then examine them, measuring their length, reproductive status, and general health. To track their whereabouts, they attach tiny transmitters to the backs of the animals before releasing them back into the wild.

Bats are “ecosystem indicators” that help scientists understand the health of our environment, Doty said. They provide many benefits, including pest control, seed dispersal and pollination. Yet they are terribly misunderstood.

Contrary to popular belief, they are docile and rarely attack humans, she said. Among more than 1,400 bat species, most primarily eat insects like mosquitoes and moths, not human blood. They have decent eyesight, but use echolocation, a form of bat sonar, to detect objects and obstacles in their paths.

“I have been in caves with thousands of bats, and never once has one come at me,” Doty said. “Bats have no interest in being around humans.”

Doty, a native Sacramentan who hails from a family of attorneys, knew at a young age that she would take a different path.

“I honestly love every animal, and I knew I would go into wildlife science,” she said. “But I happened to choose bats, and it’s very hard to move away from them.”

(Click on the images below to enlarge them. Story continues below the gallery.)

Doty has studied bats across the United States as well as faraway places like South Africa and Australia, where she earned her Ph.D. in Zoology and Animal Biology.

One of her current students, Jonathan Janes, got hooked on bats after taking an undergraduate course Doty led at CSU Bakersfield.

After learning how to handle bats for the first time in the field, “I knew that this was what I wanted to do,” Janes said. “I began to understand how important and intrinsically valuable bats are to the environment.”

Janes followed Doty to Sac State in 2022. While earning his graduate degree, he is working as a bat biologist, consulting with private and public agencies on projects around the country.

Bats are abundant in Northern California, although most of the time they are camouflaged or hidden. They reside in trees, caves, under bridges and even in leaf piles. Those native to California are mostly small, though others around the world have wing spans of up to 5 feet.

One of the best places to spot bats in the region is along the Yolo Causeway between Davis and Sacramento. The area is home to the largest colony of Mexican free-tailed bats in California, with as many as 250,000 of them roosting under the bridge in the summer months and swirling in the sky at dusk. Bats also inhabit the Sac State campus.

Occasionally, bats lose their way and wind up inside of buildings. If that happens, “just open the windows and doors, turn off the lights and let them find their way out,” said Doty. “They won’t fly into your hair. They’re probably scared.”

Public perception of bats is improving as word has spread about the benefits they provide, Doty said. In her lab, which is decorated with a neon bat and other bat paraphernalia, Doty stands as one of their biggest advocates.

“We’re starting to turn the corner,” she said of the animals’ improving reputation.

“I mean, bats are so cool if you understand them. I just love them!”

Some bat species Anna Doty has studied in the wild include (left to right) Cape serotine bats from South Africa (courtesy Anna Doty), sucker-footed bats (courtesy Manuel Ruedi via iNaturalist), tricolored bats in Arkansas (courtesy Anna Doty) and Honduran white bats (courtesy Bat Conservation International).

Media Resources

Faculty/Staff Resources

Looking for a Faculty Expert?

Contact University Communications

(916) 217-8366

communications@csus.edu