Story Content

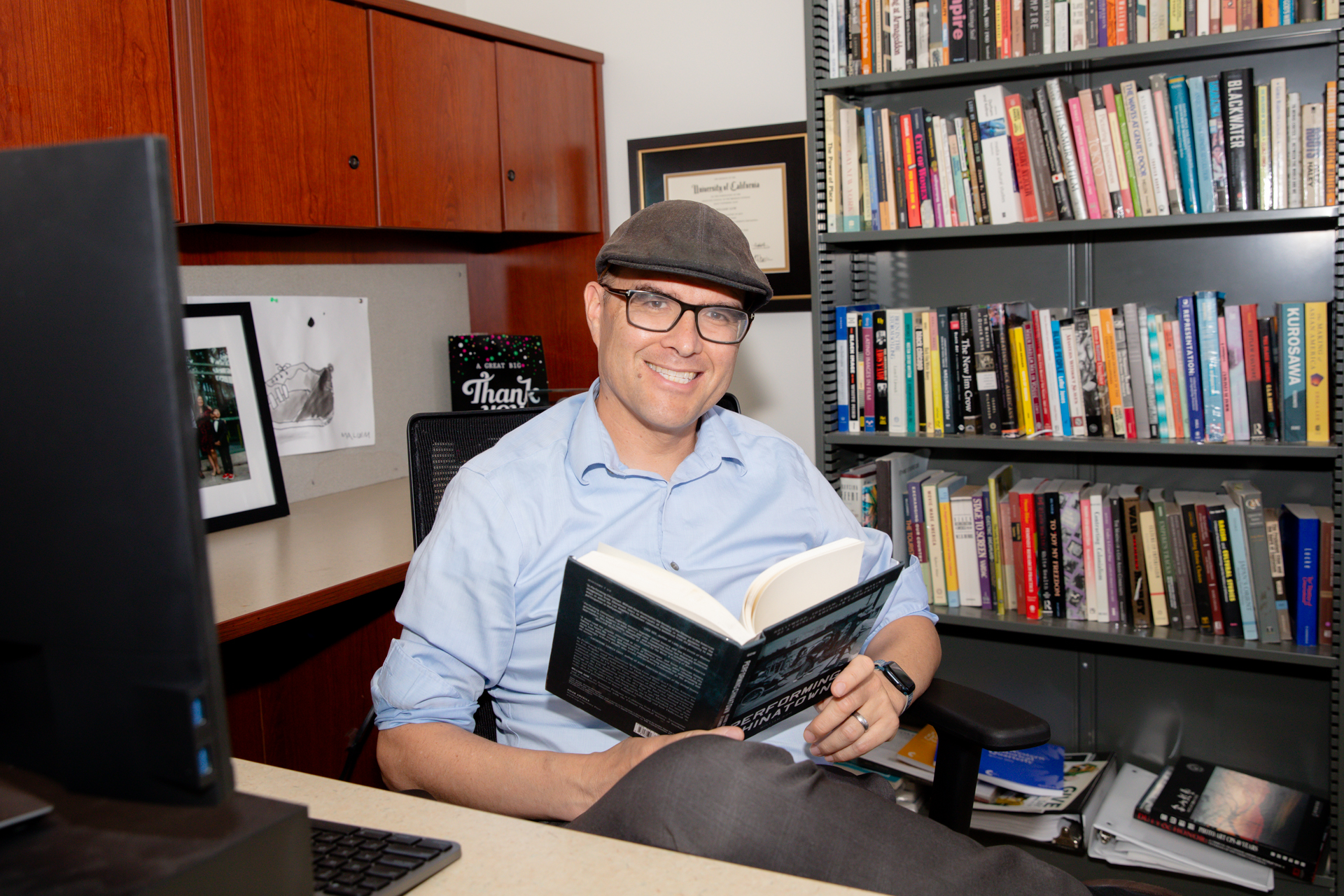

Ethnic Studies professor’s new book recounts how two L.A. Chinatowns affected tourism, business

June 12, 2024

Most visitors give little thought to the red lanterns strung across rooftops in Chinatowns throughout the U.S.

The pagoda-style buildings and chop suey menu fonts come across as charming if not fake.

But it turns out there is a story behind what Sacramento State Ethnic Studies Professor William Gow calls “Chinatown pastiche.”

In his new book, Gow shows how Chinese American merchants reshaped Chinatown’s image, attracting white tourists – and their money – while pushing back against so-called “yellow peril” stereotypes.

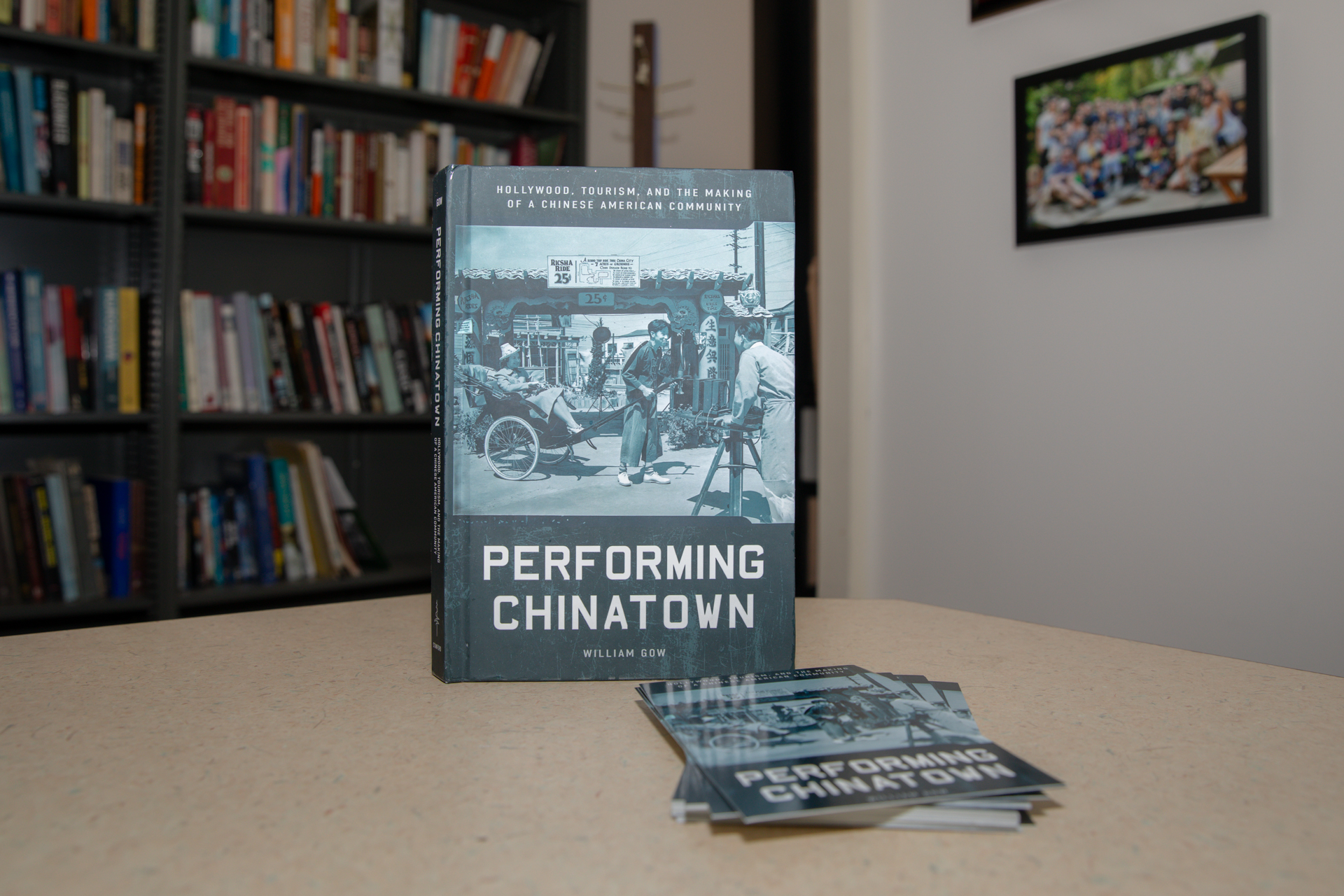

“Performing Chinatown: Hollywood, Tourism, and the Making of a Chinese American Community” explores the emergence of two Los Angeles Chinatowns and tells the overlooked stories of Chinese American movie extras and street performers during the 1930s and ‘40s.

Gow’s interest in L.A. Chinatowns began while he was a public school teacher and volunteering for the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California. He helped produce a short documentary about a little-known Chinese American community that once existed at the intersection of East Adams and San Pedro streets in the area now called South L.A.

“Chinese merchants laid the groundwork to make Chinese people more acceptable within the U.S. by creating this American-style Chinese culture.” -- William Gow, Sacramento State Ethnic Studies professor

He ended up running a program for the historical society that trained high school and college students to interview local elders about their memories of Chinatown in the '30s and ‘40s, and a common thread emerged.

“All the people we interviewed had been extras in Hollywood films during this time. Literally every single person. It was a thing,” said Gow, who has a master's degree in Asian American studies from UCLA.

“I was very well versed in Asian American history by the time I came out of UCLA, but we didn’t spend much time talking about local Asian American history. I didn’t know any of this stuff.”

Gow talked to his uncle, who had grown up in a Los Angeles Chinatown.

“He said, ‘Yeah, I was an extra in a movie.’ I saw my uncle all the time growing up. He was the first person to RSVP for our wedding, and I had no idea,” Gow said.

“It’s such a cool and interesting part of history. There were so many angles to this. I knew if I ever went back to school and got my Ph.D., I was going to do my research project on this.”

Their stories became the inspiration for Gow’s book and influenced how he later taught Ethnic Studies at Sac State.

Beginning in the late 19th century, Chinese in the U.S. faced exclusionary laws that restricted where they lived, where they traveled, who they married. Anti-Asian laws also targeted their businesses, and Chinatowns were portrayed as dirty, violent, drug-infested neighborhoods.

Off-duty police officers gave the first tours of Chinatown to middle- and upper-class white Americans who were “slumming,” according to Gow.

“Merchants watching this said, ‘We need to make money off this,’ ” Gow said. “They took the notion of exotic China and played it up, while fighting to dispel these other ‘yellow peril’ stereotypes.

“Fortune cookies, fake pagodas and chop suey menu lettering all attempt to sell ‘Chinese-ness’ to white tourists in a way that the merchant class can profit off of, while pushing back against negative stereotypes.”

In his book, Gow discusses the emergence of two L.A. Chinatowns in the summer of 1938. China City, built by white philanthropist Chirstine Sterling, was backed by the L.A. Times and Hollywood producers when it opened near Olvera Street complete with a re-creation of “The Good Earth” movie set.

Chinese Americans who ran stalls and operated rickshaw stands also worked as background extras in Hollywood films in the ‘30s and ‘40s.

Peter SooHoo and Chinese American merchants formed a corporation to create New Chinatown, a walkable neighborhood near downtown with pagoda-style rooftops, neon lights and a wishing well.

China City burned down a decade after opening, but New Chinatown still exists.

The two Chinatowns and this “Chinatown pastiche” changed the perception of Chinese in the U.S., Gow said.

“The general argument is that once the U.S. allied with China during World War II, there was geopolitical incentive to start treating Chinese people better. There’s a shift that happens overnight after the Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor,” he said. “But that’s not what happened at all.

“Chinese merchants laid the groundwork to make Chinese people more acceptable within the U.S. by creating this American-style Chinese culture.”

Gow’s research relied heavily on interviews with everyday Chinese Americans.

Historians traditionally focus on written documents, but that is not always the case when it comes to researching marginalized communities. That is because newspapers and government documentation often provide biased accounts and information, Gow said.

Media coverage of New Chinatown was minimal compared to the L.A Times-backed China City.

“If I relied on the L.A. Times and other written records, I wouldn’t know there was a New Chinatown,” said Gow, who looked at 165 oral history interviews conducted by UCLA students in the late 1970s.

But interviews he and his students conducted with more than 40 people for the Chinatown Remembered project unearthed the Hollywood angle.

“It kept popping up,” Gow said. “I could not tell this story without those oral histories.”

Gow’s Ethnic Studies class at Sac State requires students to work in groups and interview Asian Americans in the community about their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. So far, there are 77 interview transcripts and some audio recordings available to the public online.

“Oral history is my passion. It’s the wave of the future,” Gow said.

Media Resources

Faculty/Staff Resources

Looking for a Faculty Expert?

Contact University Communications

(916) 217-8366

communications@csus.edu