|

Early morning light catches the peaks of the Sangre de

Cristo range. The earth begins to glow.

As sunrise pushes back the night, the town below is

revealed as a patchwork of brown, pink and beige.

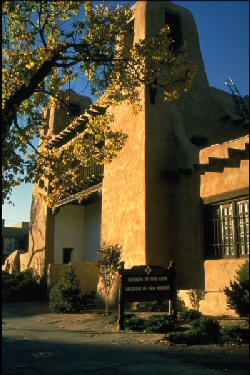

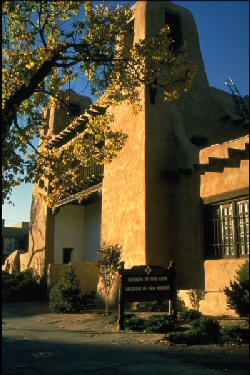

The uniform style and colors of the buildings in the

town induce a sense of being welcomed and even embraced.

The word connection comes to mind.

To see it is to feel it. The long, clean, gently

broken horizontal lines of the clustered, low-slung

Pueblo/Spanish-style buildings produce a network of

intersecting lines. They are like cords of energy

binding people to the earth and linking them to the

emerging daylight.

For a moment, you think, "This can't be America,

1998. I've time-traveled."

And then you see the cars and remember that time

travel hasn't been invented.

This is here and this is now, but this is also Santa

Fe, a town so easy on the eyes and soothing to the soul

you want to call it natural, traditional, authentic,

real.

And yet it's so totally, completely . . . artificial.

Structures with a design borrowed from Native America

and Spanish America house businesses ardently

Anglo-American: dry cleaners and dime stores, art

galleries and restaurants.

The Euro-Americans who

dominate the region are not here to live like Native

Americans but like modern global citizens in "let's

pretend" surroundings.

Certainly, it's not real to surround yourself with

out-of-date architecture and live shut away from the

strip-mall, fast-food higgledy-piggledy world of today?

This is not authenticity - this is escape.

Face it: If the Disney organization built a

SouthwestLand, it would look like Santa Fe with theme

rides.

In fact, the entire enterprise called Santa Fe was

decreed from its modern origins as a kind of

SouthwestLand. In The Myth of Santa Fe: Creating a

Modern Regional Tradition (University of New Mexico

Press, $39.95), author Chris Wilson explains that

the

"natural" look of present-day Santa Fe is the result of

a conscious strategy to attract tourists.

At the turn of the 20th century, Santa Fe was sinking

in financial stagnation, and city fathers saw the

creation of a historical throwback in the middle of the

desert as potential salvation.

"By 1920, an unwritten consensus formed that all new

buildings should employ the Pueblo-Spanish style," with

some Territorial additions in the 1930s, Wilson writes.

Ironically, this required a reversal of trends. In

the late 19th century, Santa Feans had built with adobe

and disguised the result as more-acceptable brick or

frame structures. Now,

everything had to be disguised as

adobe, even buildings made with brick. A city ordinance

in 1957 confirmed by law what had long been in effect by

common agreement: that Santa Fe would, to the greatest

degree possible, look as it did before 1860, when the

increasing Anglo population brought East Coast-style

buildings to the area.

Is Santa Fe for real? Not in the sense that

architects w ould use "real."

"Honest use of materials," the famous maxim of modern

architecture, is violated by Santa Fe's architectural

raison d'etre: adobe in looks if not in actuality.

The authentic item is easy to make. Go to tiny

Tesuque Pueblo (population 425) most days in summer, and

you'll find laborers making and building with adobe

bricks. The mud is mixed with hay in a tumbler, pressed

and cut into squares and set out to dry.

The drying takes anywhere from a few days to a few

weeks, depending on humidity.

Then the buildings go up. A small, rectangular home

was under construction when I stopped by - simplicity of

material matched by simplicity of design. This is

natural and real and second nature to the people who

have lived in Tesuque Pueblo for centuries.

For the people to the south in Santa Fe, it's exotic.

So they come - some to stare, some to stay - and they

don't seem to mind or even notice the artificiality of

their surroundings.

Pianist-composer Marc Neikrug came to live in Santa

Fe in 1990. He's now artistic director of the

prestigious Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival. It was

Neikrug who first mentioned to me The Myth of Santa Fe,

acknowledging the town's fabrication as a sort of

high-class tourist mecca. So, why, of all the places

that he, as musician, might have settled, did Neikrug

choose to move here?

"Simply because it is the most beautiful place I've

ever been," he said.

And he meant the "artificial" town ambience right

along with the elevating natural environment.

Artists of every discipline have agreed with

Neikrug's

assessment. First came the painters, settling

in Santa Fe and its smaller mirror image to the north,

Taos. John Sloan, Marsden Hartley, Ernest L.

Blumenschein, Victor Higgins and others explored the

region in the teens and '20s, painting the shapes of the

mountains and clouds. Georgia O'Keeffe arrived in 1929,

synthesized all that had come before and developed the

iconic vision of earth tones, cow skulls and sky-blue

vistas many carry with us as "New Mexico."

Photographers followed. Ansel Adams claimed the

landscape for his own, using his famous technical

methods to capture the richness of New Mexican light in

black and white.

Then came the writers. D.H. Lawrence found the Indian

energy in affinity with his own sense of the life force;

his ashes are interred at Taos.

Novelist Willa Cather portrayed the nobility of Santa

Fe's 19th-century Archbishop Lamy, whose faith and will

forged the building of Santa Fe's Romanesque St. Francis

Cathedral, in Death Comes for the Archbishop.

The moneyed, New England-born poet Witter Bynner made

Santa Fe home from 1922 to his death in 1968. Artificial

or real, Santa Fe to him was a spiritual preserve in a

materialist world. He celebrated this in his poem Santa

Fe:

Among the automobiles and in a region

Now Democratic, now Republican,

With a department store, a branch of the Legion,

A chamber of commerce and a moving van,

In spite of cities crowding the Trail,

Here is a mountain town that prays and dances

With something left, though much besides may fail,

Of the ancient faith and wisdom of St. Francis.

The major religion of the area in recent history has

been Roman Catholicism, but the spirituality of the

place is ecumenical. The Anasazi, perhaps ancestors to

the Pueblo Indians, lived in the area for a thousand

years before the Spanish founded Santa Fe in 1609-1610,

and Native American ceremonies still thrive in the

surrounding pueblos. New Age psychics also abound.

The arts continue to be important. Classical music is

big business in the summer, with the Santa Fe Opera

(505-986-5900) and Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival

(505-983-2075) playing to consistently sold-out houses

for months.

Canyon Road near the center of Santa Fe is crowded

with galleries showing the work of the latest hopefuls

to succeed O'Keeffe and company. O'Keeffe's work is now

the stuff of one of Santa Fe's most visited shrines, the

Georgia O'Keeffe Museum (505-685-4539).

The current energy of Santa Fe's visual arts is most

readily visible in 3-D at Shidoni (505-988-8001), a

sculptural center in the town of Tesuque, five miles

north of town.

Its sprawling sculpture garden displays whimsical and

realistic work of massive scale. At certain times,

visitors can watch bronze poured and cast.

The strategy to make Santa Fe attractive to tourists

has certainly worked. The 4,000-plus hotel rooms here

can barely accommodate summer visitors. Tourists pay

close to $100 million annually just for accommodations.

Some would say it has worked too well, with Santa

Fe-style in architecture and dress and food having

become a coyote-ridden cliche.

Yet humans are fabricators, and everything we make is

artificial. Towns and cities of any character are myths

created by people to suit their aesthetic or commercial

or political needs.

Manhattan is a myth. So is Seattle. Bank One Ballpark

could be the beginning of a Phoenix myth.

We Americans tend to confuse real with practical,

arming ourselves with a prejudice against the beautiful

and the creative.

Perhaps the best way of being real is

being artificial. It works for Santa Fe. |