Space and Time

Space, Time and Infinity

PHIL 192D

Spring semester 2019

Prof. Dowden

Prerequisite(s):Catalog

description:

Introduction to significant philosophical issues involving space and time. An investigation into the current state of these issues.

Note:

No background or work in mathematics or physics is required. Cross-listed: HRS 205; only one may be counted for credit.

Grades:

Two class presentations (6% and 15%),

three essay assignments (10%, 23%, 23%), and a final exam (23%).

- Essay 1 due Feb. 7, 2019 (week 3).

- Essay 2 due Mar. 28 (week 9).

- Essay 3 due April 25 (week 13).

- Final Exam (week 16).

Depth of philosophical insight, accuracy of information, and quality of argumentation are the paramount factors affecting the essay grades, but English writing skill is also a significant factor.

On the day of your chosen class presentation (for 15% of your total grade), you will be the teacher for 15 minutes. Begin with about a ten minute presentation to the other students on some part of that day's course material. End by proposing one or two questions for group discussion on the material, and then facilitate this discussion for about five minutes. The presentation should be an introduction that explains the main points made in one or more of the required readings or viewings for that day. Before 7:00 pm on the night before your presentation, email an outline to me at dowden@csus.edu. The outline should list at least six separate phrases (or sentences), followed by two discussion questions that are related to the philosophical material in your presentation and that you plan to ask the class. A sample outline of a presentation is available in Canvas. You will be given automatic enrollment in the Canvas portion of our course once you are officially registered and the semester has begun. A sign-up list for Student Presentations that will be distributed on the first day of class.

The 6% class presentation

to the class is a five-minute summary of what happened in the previous class period not counting the student presentation at the beginning. You cannot choose to report on your own previous presentation. You do not have to respond to students' questions about your summary.

Your presentation will normally be given at the beginning of the class period.

There is a signup list within Canvas.

Textbook:

There is no textbook to purchase.

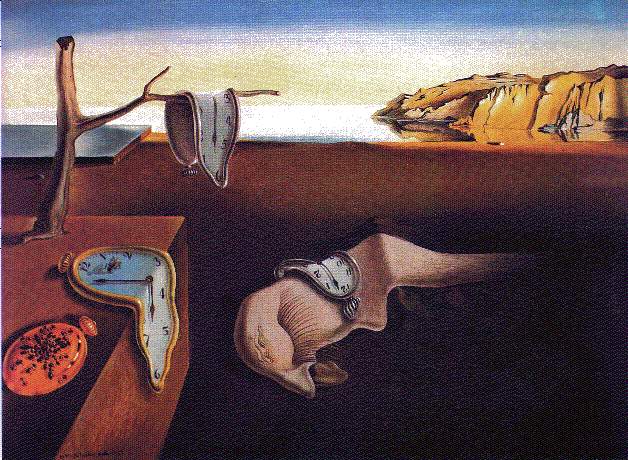

Here is an optional, helpful,

inexpensive textbook for about one-third of the course: Introducing Time by Craig Callender and Ralph Edney. 2001, 2005. Any edition of this book is OK;

tthat is, don't worry if your book's cover is different from the

one pictured below because all editions have the same content.

Introducing Time is a book of many pictures with some words. It is written by a famous American philosopher of time. The Introducing Infinity book in the same book series is to be avoided.

Required reading and

viewing assignments are described in the

weekly schedule of assignments.

Some of these reading and viewing assignments refer to items in Canvas;

for these, look in the Modules section in the left column of the Canvas

homepage.

Our course is about space. What sort of space?

Not just outer space. If you have a cubic box, one foot on an edge, and you fill it with marbles, then how much space is there in the box? There are two answers: (1) A cubic foot. (2) It depends on how big the marbles are. Our course is about space

only in sense (1). We will explore theories of the origin of space and

the variety of ways to answer the cosmic question "Why is there

something rather than nothing?" We will explore the fourth dimension,

parallel universes, the surprising ways that space acts upon matter, the

ways space can change its shape, why space might actually emerge from

something more fundamental, and how particles

in distant

locations can be entangled with a bond that transcends the intervening

space. Think about some distance d in space. Do you know for sure

that there is such a thing as half of d? Why? No measurement

could say for sure that half of d exists, since all

measurements have a margin of error. How about a distance that is d

times the square root of two? Does it exist? How do you know? There are

good answers to these questions, but they are subtle.More detailed course

description:

Our course is about time. We don't mean free time,

nor time management. We mean an investigation into what clocks are used to measure. Consider this one issue upon which philosophers are deeply divided: What sort of ontological differences are there among the present, the past and the future? There are three competing theories. Presentists argue that necessarily only present objects and present experiences are real, and we conscious beings recognize this in the special vividness of our present experience compared to our dim memories of past experiences and our expectations of future experiences. So, the dinosaurs have slipped out of reality even though our current ideas of them have not. However, according to the growing-past theory, the past and present are both real, but the future is not real because the future is indeterminate or merely potential. Dinosaurs are real, but our future death is not. The third theory is that there are no objective ontological differences among present, past, and future because the differences are merely subjective. This third theory is called “eternalism.”

Only one of these three competing theories can be correct.

Here are some of our other philosophical issues about time: What time actually is; Whether time exists when nothing is changing; Whether both forward and backwards time

travel are physicallly possible; Why time has an arrow; and how to correctly analyze

the metaphor of time's flow. Our course will unravel many of the

mysteries of time.

Our course is about infinity. There is no end to the strangeness of the infinite. To prepare you for what is to come on that topic, here is a quotation from the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges: "There is a concept which corrupts and upsets all others. I refer not to Evil, whose limited realm is that of ethics; I refer to the infinite."

We will explore why the French philosopher Blaise Pascal said the infinite is something "not to understand, but to admire."

Our exploration of the infinite will encounter the following issues and more: How has Aristotle's concept of potential infinity fared since its encounter with the 19th century concept of actual infinity which says a set of things is infinite if it can gain or lose some things and still be the same size? Was Gauss, who was one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, correct when he made the controversial remark that scientific theories involve infinities merely as idealizations and merely in order to make for easy applications of those theories, when in fact all physically real entities are finite? How did the invention of set theory change the meaning of the term "infinite"? What did Cantor mean when he said some infinities are smaller than others? Was Quine correct when said the first three sizes of Cantor's infinities are the only ones we have reason to believe in? What are we assuming when we say there are fractal curves that enclose a finite area but have an infinite circumference? What are the best candidates for four objects that are infinitely large, infinitely small, infinitely numerous, and infinitely divisible?

Here are three more examples of some of the philosophical issues that we will explore in our course:

- Without minds in the world, nothing in the world would be surprising or beautiful or interesting. Can we add that nothing would be in time?

- If all the stuff were to be removed from space, would empty space still be left, or instead would even empty space be gone?

- Is the concept of "the infinite" such an awesome concept that we finite humans cannot understand it?

These and many other issues of ours will be placed in historical context, but

they won't be covered in chronological order. Still, the course's historical range is broad. For

example, we will discuss the Greek philosopher Zeno. Working with the infinite is tricky business, and Zeno’s paradoxes first alerted philosophers to this in 450 B.C.E. when Zeno argued that a fast runner such as Achilles has an infinite number of places to reach during the pursuit of a slower runner. Since then, there has been a struggle to understand how to use the notion of infinity in a coherent manner.

Has the struggle been successful?

There will be significant attention given to what has been learned about

space, time, and infinity since the beginning of the 21st century. The relevant

mathematical and scientific theories will be introduced as needed, but informally, with an emphasis on the philosophical controversy.

Reality is not what it seems. Regarding the philosophical issue of travel through space, the most important point for you to remember is that wherever you go on a trip, there you are.

Your luggage is another story. Schedule of Topics and Assignments:

The schedule of weekly topics with the reading and viewing assignments is

here.The schedule of class presentations will be created during the first week and then posted in

Canvas.

Instructor:

My office is in Mendocino Hall 3022. My weekly office hours there are Tuesday and Thursday 10:45

A.M. - noon. Feel free to stop by or to

telephone at any of those times. If those times are

inconvenient for you, then we can arrange an appointment for

another time. I also have office hours online within Canvas every Wednesday night

9 - 10 P.M. Usually the fastest way to contact me is not by telephone

but rather to send e-mail to

dowden@csus.edu.

You can expect a response to your email within 24 hours, usually sooner. My personal page at http://www.csus.edu/indiv/d/dowdenb/index.htm has the telephone number of my secretary, a mailing address, and other information about me.

click photo to expand

Late work, and make-up

assignments:

I

realize that during your college career you occasionally may be unable

to complete an assignment on time. There will be no make-up or extra-credit projects. I do accept late assignments with a grade

penalty of one-third of a letter grade per 24-hour period beginning at

the class time the assignment is due.

Here are some examples of how this late penalty works.

If you turn in the assignment a few hours after it is due, then your A becomes an A-.

Instead, if you turn in the same assignment 30 hours late, then your A

becomes a B+. Weekends count, so scan and email your essay as soon as it is finished. No late essay will be accepted

after the answer sheet has been handed out or posted within Canvas (often this will be at the

next class meeting after the due date) nor after the answers are discussed in class, even

if you weren't in class that day.

Add-Drop:

To add the course, try to do so by using

“My Sac State” (https://www.my.csus.edu) . If

the course is full, then see me about signing up on the waiting list.

To drop the course during the first two weeks, use My Sac State. No paperwork is required. After the first two weeks, it is harder to drop, and a departmental form is required, the "Petition to Add/Drop After Deadline." As with any university course, make sure you are dropped officially; don't simply walk away into the ozone or else you will get a "U" grade for the course, which is counted as an "F" in computing your GPA (grade point average).

Disabilities:

If you have a documented disability and

require accommodation or assistance with assignments, tests,

attendance, note taking, etc., please see me early in the semester so

that appropriate arrangements can be made to ensure your full

participation in class. Also, you are encouraged to contact the

Services for Students with Disabilities (Lassen Hall) for additional

information regarding services that might be available to you. See also http://www.csus.edu/sswd/index.html.

Plagiarism and Academic Honesty:

Browse the University's policy on academic honesty .

Food in class:

Except for water, please do not eat or drink during class time. You are welcome to leave

class and return anytime if the need arises.

Student outcome goals:

The goal is for you to acquire a broad understanding of the major philosophical issues that involve the nature of space and time and infinity. You will know what is controversial about various important claims that have been made, you will know the major arguments in defense of these claims, and you will be able to carefully express and to defend your own views on these topics.

Laptops and cell phones:

Photographing during class is not allowed. Audio recording is OK. During class, turn off your cellphone's ringer. Your computers may be used only for note taking, and not for browsing the web, reading emails, or other activities unrelated to the class. If you use a computer during class, then please sit in the back of the room or on the end of a row so that your monitor's screen won't distract other students. Educational research shows that students learn more when they take notes by using a pencil or pen rather than by typing.

Updated: February 17, 2019