Andrew Stoner

Andrew StonerAcceptance of the LGBTQ community has evolved considerably since the era of pioneering journalist Randy Shilts. But that evolution was in its early stages in 1986.

That’s the year Andrew Stoner, now a Sacramento State professor of Communication Studies, graduated journalism school. Just before graduation, Stoner recalled, he had a conversation with one of his professors. As a prospective young reporter, Stoner considered the labor and planning he had put into his craft, but wondered if another factor would determine his fate: What if his bosses learned he's gay?

“Are they going to fire me?” Stoner wondered.

The professor advised that Stoner “not lead” with that disclosure and simply do his job.

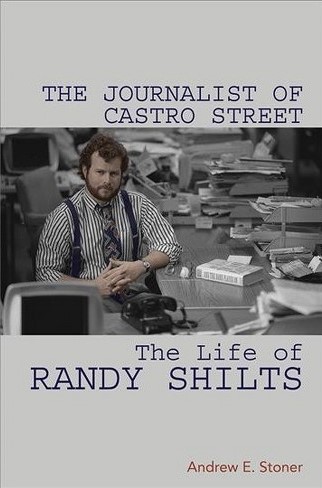

Such stories, though not entirely obsolete in all workplaces, are unheard of in newsrooms today. Shilts, generally acknowledged as the first openly gay reporter at a major daily, paved the way for people like Stoner. Shilts’ equally important place in American journalism was his reporting for the San Francisco Chronicle on the emerging AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s. Stoner examines both in a new biography, The Journalist of Castro Street: The Life of Randy Shilts.

- Hear Andrew Stoner discuss his biography and Randy Shilts in a San Francisco Chronicle podcast

- Read an excerpt of The Journalist of Castro Street at Literary Hub.

- The Chicago Tribune’s review

- From the Seattle Book Review

The book, which began as Stoner’s doctoral thesis at Colorado State University, draws on more than 100 interviews, cooperation from the Shilts family, and deep research that included two weeks sifting through Shilts’ archive at the San Francisco Public Library’s Hormel Center.

The bio is something of a “reconsideration” of Shilts, Stoner said. His admiration for Shilts, who died in 1994 at age 42, is clear, but Stoner avoids canonizing the reporter. The light in which Shilts is cast continues to evolve, Stoner said.

The latest book by Sacramento State Professor Andrew Stoner.

The latest book by Sacramento State Professor Andrew Stoner.“When he died in ’94 he was well thought of,” Stoner said. Shilts’ 1987 book, And the Band Played On, is considered the definitive chronicle of the AIDS epidemic’s early years. But later criticisms of it point to its misplaced focus on a French-Canadian flight attendant, Gaëtan Dugas, as the person who brought HIV to the United States -- “Patient Zero.”

Stoner said that although Dugas was directly linked to about 100 cases of what was then known as gay-related immune deficiency (GRID), it has been since proven that Dugas did not bring HIV to the U.S.

“We had this virus in America probably as early as 1967,” Stoner said. “Dugas would have been a little boy then.”

Shilts didn’t exactly push the theory of Dugas as Patient Zero, but he didn’t explicitly refute it either. As a result, Stoner said, Band “has this huge hole.” (The belief that Dugas was responsible for bringing HIV to the U.S. arose because of a widespread misinterpretation of the letter “O” for “Outside Los Angeles,” as Dugas’ case was labeled in one study, as the digit “0.”)

Stoner also confronts Shilts as a flawed human who battled drug and alcohol addiction.

Today, Shilts is considered a newsroom culture trailblazer, Stoner said, who also provides an ideal case study of the importance of balancing strongly held personal beliefs about an issue and using one’s reporting to advance that position, something Shilts struggled with.

“He hated being called an advocate,” Stoner said, “but I think he clearly falls within that category of using journalism to advance the things he thought were important. We see a lot of that happening today.”

Shilts’ approach sometimes led him to butt heads with the community he covered. His stories portrayed the gay rights movement as being about more than sexual freedom. He roiled the gay community with stories about “out of control” STD/STI rates among gays and his stance in favor of closing San Francisco’s popular men’s bath houses.

“He accused the gay community of being more concerned about AIDS as a PR problem than an actual threat,” Stoner said.

This is Stoner’s second biography and eighth book. His next will be about George C. Wallace, the segregationist Alabama governor who four times unsuccessfully sought the Democratic presidential nomination, and who won five states and 46 electoral votes in 1968 as a third-party candidate. Wallace died in 1998.

“Somebody asked me if I’m drawn to people who need more examination,” Stoner said.

Stoner said he sees another contemporary connection to Shilts’ work in the way society tends to seek out and make pariahs of “the other.” He finds a parallel in “Patient Zero” then and “illegals” today – a terminology he said assigns a virus-like characteristic to people.

“It’s a convenient way to organize it in our heads,” Stoner said, “but not particularly fair, or good, or decent – or accurate, really.”

Stoner marvels at Shilts' ability to see around the corner. Shilts' last book, 1993’s Conduct Unbecoming, was about gays in the military, a huge issue in the last presidential election of his life in 1992. His next project was going to be about alleged sex abuse in the Catholic Church.

“He’s always so amazingly on key,” Stoner said. “I hope that by retelling his story and retelling the struggles he went through as a journalist and as a person will help further our understanding of the reporter’s role in society and how media struggle to cover complex stories like this. My hope is a whole new generation will discover who he is.” – Ahmed V. Ortiz