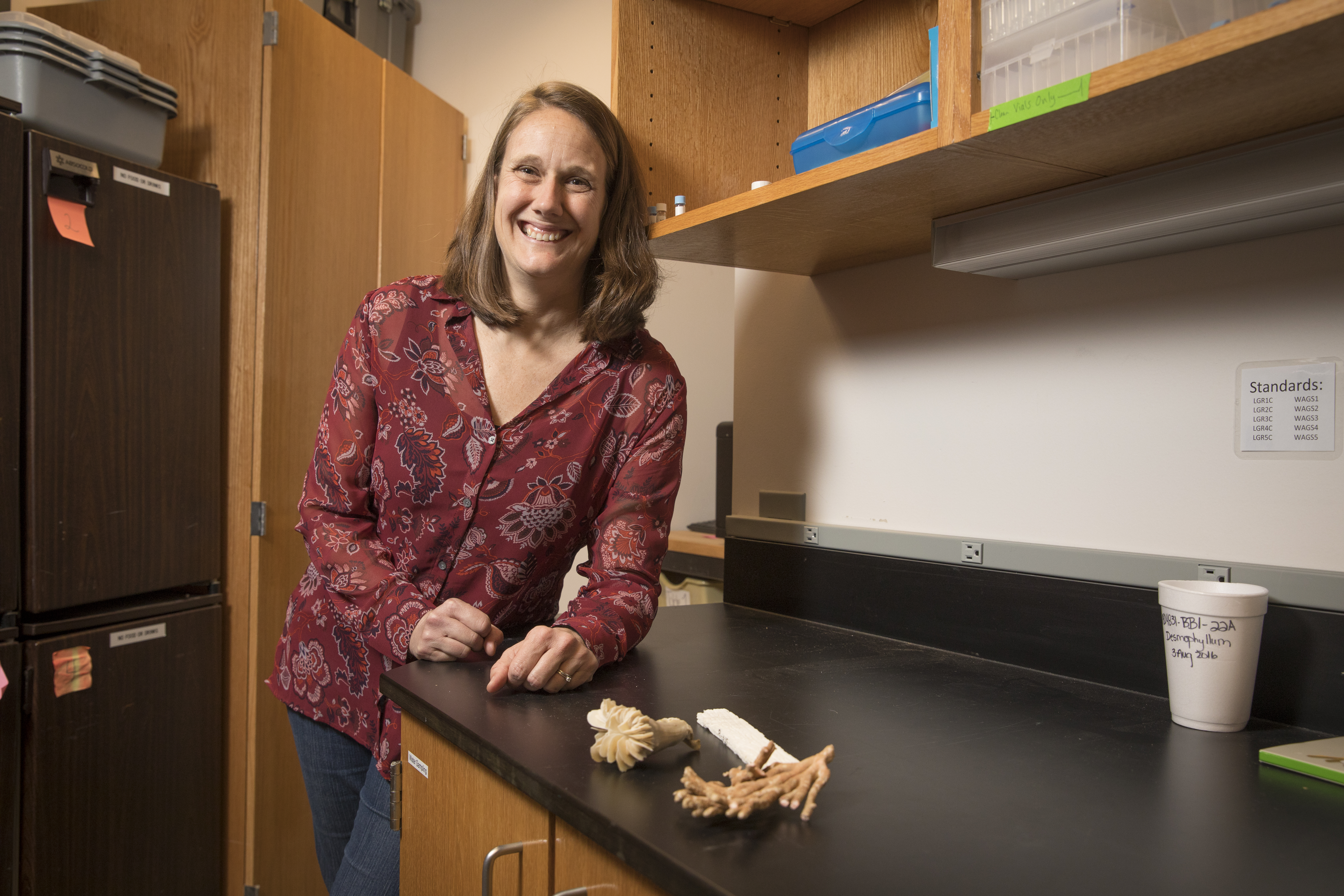

Assistant professor of geology Amy Wagner is part of a team of researchers who are finding more clues about climate change by bringing them up from the ocean depths. (Sacramento State/Andrea Price)

Assistant professor of geology Amy Wagner is part of a team of researchers who are finding more clues about climate change by bringing them up from the ocean depths. (Sacramento State/Andrea Price)The ocean speaks volumes to scientists like Sacramento State’s Amy Wagner.

At its surface, it offers information about the health of our planet. On its floor, it reveals glimpses of the distant past.

Layer by layer, it tells a story about the impact of climate change, a topic of great interest to Wagner, an assistant professor of geology, and scientists around the world.

Aboard a 274-foot research vessel named the R/V Thomas G. Thompson, Wagner and 21 other researchers recently steamed to the Indian Ocean, where they spent weeks in remote locations collecting water and sediment from the depths. The international research team, led by chief scientist Elisabeth Sikes of Rutgers University, returned with a trove of samples that they will analyze in their laboratories in an effort to reconstruct past ocean conditions, and possibly help forecast the future.

- Learn about Professor Wagner's latest expedition, Windows to the Deep 2019 (with live video)

- Article by Professor Wagner and others on Leg 2 of Windows to the Deep 2019

Along with their massive significance to the world at large, oceans are one of the most important areas of research for climatologists.

Studies already suggest that climate change, most likely spurred by human activity, is affecting the world’s oceans. A study published in January in the journal Science found that ocean warming is accelerating faster than previously thought, with dire implications. Escalating water temperatures have been blamed for killing marine ecosystems, raising sea levels and making hurricanes more destructive.

Wagner and her collaborators are seeking to build on such research, gathering information that can be used to map ocean conditions over time to gauge their health and the effects of a warming world. Her primary focus is paleoceanography, the study of the history and evolution of oceans through the lenses of water circulation, chemistry, biology and sediment patterns.

On the most recent voyage, which spanned 45 days and ended just before Christmas, she and her shipmates traveled from their port in Western Australia across two oceans and nearly halfway to Antarctica. The scientists worked in shifts, with Wagner, serving as a "watch leader" or senior scientist, on duty from midnight until noon.

Their bounty? Huge pipes full of mud from the bottom of the Indian and Southern oceans. Their eventual goal? To document climate conditions since the last ice age.

“These samples will keep scientists and students very busy for a long time,” Wagner said in an interview in her Placer Hall office in early January. “Many years of research will come out of this cruise.”

The mission was just the latest in a series of exotic adventures for Wagner, a former “desert rat” from Phoenix who discovered early in life her passion for the ocean and its inhabitants.

“When I was a kid, my older brother had a sailboat in Oceanside,” she said. “I fell in love with being out on the water.”

Wagner studied marine science and oceanography at Texas A&M University, earning bachelor's, master’s and doctoral degrees before joining Sac State’s faculty in 2013. Her career has taken her on research missions around the world, including all seven continents.

“When you’re in the middle of the sea with no other living beings in sight, it helps put life in perspective,” she said. “It makes you realize that we are just specks in this world. For some, that’s unsettling. But for me, the ocean is very calming.

“I look out at that grandeur, and it motivates me to want to help preserve it.”

Wagner’s work has focused on corals, both the brightly colored ones from warm tropical waters and the more muted variety harvested near Antarctica, among other locations.

Coral locks the chemistry of the ocean into its skeleton, she explained, and offers insights into conditions hundreds or even thousands of years ago. Scientists use radiocarbon dating and other geochemical techniques to analyze sea temperatures, salinity and other chemistry within the skeletons, collecting data that can be used in climate models and forecasts. Some coral Wagner has collected dates back several thousand years.

Similar analyses can be applied to samples of sediment and water extracted from the ocean, she said.

Aboard the Thompson, Wagner helped oversee collection and preservation of samples from different ocean depths across a range of latitudes. Each layer of water, she said, has its own chemical properties that offer insights into the ocean’s health at various times.

The Thompson team gathered its raw research material through "coring," a complex process of grabbing ocean samples and loading them onto a ship.

Cores are giant pipes that are lowered vertically over the side of the ship with strong wire and heavy machinery to the ocean floor. There thy capture sediment and skeletons of tiny creatures called foraminifera – forams, for short – before being hauled back onto the ship.

Once retrieved, the cores are cut into smaller sections, split in half and sealed to keep them from drying out. Content of the cores is later analyzed for oxygen and carbon isotopes, among other chemical elements, that offer insights into the ocean’s temperature and health over time. Water samples undergo similar measurements.

Information gathered from the Thompson mission, dubbed CROCCA-2s for “Coring to Reconstruct Ocean Circulation and Carbon Dioxide Across 2 Seas,” has groundbreaking potential, Wagner said.

“We have no data for this part of the Indian Ocean,” she said. “This area has not really been explored before. This will give us a baseline that will help us put modern information into context” and help guide other scientists and policymakers working to stave off the potentially disastrous effects of climate change.

“Are the changes that we see today normal, part of the natural cycle?” Wagner asked. If not, they could be a symptom of climate change, which ultimately “could impact the entire ecosystem.”

The CROCCA-2s cores are currently in transit. They are to be stored at Oregon State University, and soon will be available for the mission scientists, and later other researchers, to sample and study.

The cruise and subsequent research is funded by the National Science Foundation.

Wagner plans to incorporate some of what she learned from the journey into her oceanography and marine geology courses at Sac State, and ultimately to publish a scientific paper on the team’s findings.

In the meantime, she is enjoying being back on dry land, preparing for the upcoming semester and spending time with her husband, Michael Mutmansky, an engineer, and their dogs Obsidian and Amber.

“I think the mission was very successful,” Wagner said. “I’m so grateful that my department and college supported this work, and I’m excited to bring it back to the students.” – Cynthia Hubert