Provost Ching-Hua Wang meets Mohammad Vaziri, professor of electrical and electronic engineering, at a welcome reception in her honor. (Sacramento State/Jessica Vernone)

Provost Ching-Hua Wang meets Mohammad Vaziri, professor of electrical and electronic engineering, at a welcome reception in her honor. (Sacramento State/Jessica Vernone)Dr. Ching-Hua Wang, Sacramento State’s new provost and vice president for Academic Affairs, was a member of China’s “sent-down generation,” one of 17 million youths torn from their families during the country’s Cultural Revolution that began in the late 1960s.

China’s Communist leader, Mao Tse-tung, ordered that schools throughout the country be closed indefinitely and that “intellectual youth” from middle school to college be sent away from cities and towns to perform hard labor in far-flung locales. Wang and 12 of her classmates were delivered to a tiny village in Inner Mongolia.

Day after day, month after month, Wang toiled in the fields.

“That’s where I developed into a very resilient person, a person who would not give up hope,” she says. “None of us, when we were on the farm, knew what would happen in the future, whether there would ever be schools opening up or not. However, in my heart of hearts, I wasn’t ready to quit studying.”

Wang still has the small trunk in which she carried books from her childhood home in Beijing to the village where she performed hard labor for six years. One of her most precious possessions is the Oxford English Dictionary that her father sent while she was in exile. He had been relocated to Jiangxi Province, where he raised pigs and grew cabbages.

“My father was telling me, ‘Don’t give up on learning,’ ” she says. “There was no electricity in Mongolia. Because I got this dictionary, I made a little lamp for myself using a small ink bottle. I sold eggs in the village to buy kerosene to fill the ink bottle, and every night I studied the dictionary and learned English.”

Wang (she prefers the British pronunciation “Wong”) struggled for years to pursue her education. Persistence paid off: She would earn a medical degree from Beijing Medical College, a master’s in immunology from Beijing Medical University, and a doctorate in immunology from Cornell University.

‘A student-centered person through and through’

For obvious reasons, student success is close to her heart.

“I really am a student-centered person through and through,” she says. “And what I knew of President (Robert S.) Nelsen before I applied for this position is that he is student-centered, as well. The relationship between a provost and a president is so critical to the success of a university.

“In terms of personality, we have that chemistry and that strong student-success orientation. So I think working with him will be great.”

Wang came to Sacramento State from Dominican University of California, in San Rafael, where she served as dean of the School of Health and Natural Sciences. She also was a professor of immunology and microbiology, and she managed extramural grants on the campus, raising $9.3 million from private sources and corporations.

Before she went to Dominican, she was one of the original 13 faculty members recruited to start CSU Channel Islands, in Camarillo, in 2001. In addition to teaching and doing research, she was program director for the Bridges Stem Cell Research Training Program, chair of multiple science and health science programs, and director of the Master of Science in Biotech and Bioinformatics Program. She also was a special assistant to the provost.

Wang’s introduction to the CSU had come in 1990, when she joined the faculty of CSU San Bernardino as an assistant professor of biology. By the time she left for Channel Islands in 2001, she was a full professor of immunology and microbiology, and the graduate coordinator of the biology master’s program.

Over the years, Wang visited Sacramento State for academic meetings.

“I just fell in love with the campus. I love the setting, the trees and all,” she says. “So I always knew about the University, and I had a very good impression of Sac State. This is California’s only capital university.”

Her first day at Sacramento State was Feb. 1. She is the University’s second-highest-ranking administrator.

Her husband, Nian-Sheng Huang, is a professor of colonial American history and world history at CSU Channel Islands. He plans to join his wife in Sacramento at the end of this semester.

Huang is a published author who specializes in early American history. Among his books are Benjamin Franklin in American Thought and Culture, 1790-1990, Franklin’s Father Josiah: Life of a Colonial Boston Tallow Chandler, 1657-1745, and Floating Poverty: The Poor in Eighteenth-Century Massachusetts. He’s writing his first work of fiction.

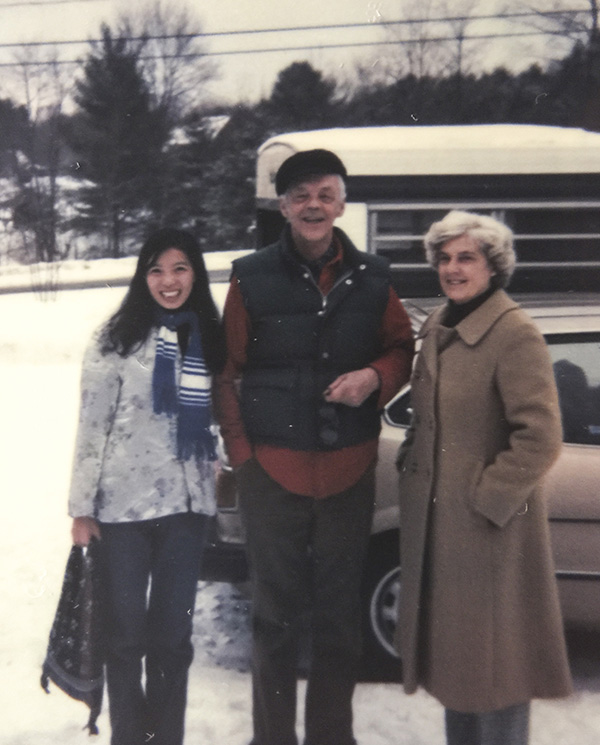

Lincoln Adams worried that his friend Ching-Hua Wang, newly arrived at Cornell University from China, would be lonely if she spent the long winter break in the graduate students’ dorm. So he invited her to Maine to spend the holidays with him and his parents, Natalie and Harry Adams. “That became my first-ever lovely Christmas experience,” Wang recalls. (Photo courtesy of Lincoln Adams)

Lincoln Adams worried that his friend Ching-Hua Wang, newly arrived at Cornell University from China, would be lonely if she spent the long winter break in the graduate students’ dorm. So he invited her to Maine to spend the holidays with him and his parents, Natalie and Harry Adams. “That became my first-ever lovely Christmas experience,” Wang recalls. (Photo courtesy of Lincoln Adams)Love and perseverance amid years of hardship

Wang and her husband have been married for 35 years. They have two children: Sha and Enid Hwang (their last name is the combination of their parents’ surnames), both born in Ithaca, N.Y., when their parents were doctoral students at Cornell. Both are working in the technology sector in New York City.

The couple have known each other since their middle school years in Beijing. Huang was one of the 13 students “sent down” to the village with her, and it was there that they fell in love.

One day while cutting wheat in the fields, Wang badly injured herself with a sharp sickle blade. The village had no medical care, and the deep gash soon became infected. The villagers, taking pity on the young girl, asked her to teach their children in the one-room schoolhouse.

She sometimes shared her food with her students, who came from families in extreme poverty. She encouraged them to continue their schooling. She knew how precious educational opportunities were to the social and economic mobility of children from impoverished families.

Three years after Wang was separated from her family, Chairman Mao allowed schools and universities to reopen across China. Her 12 former classmates began to leave the village, one by one.

“I didn’t want to go to work in the city just for the sake of earning a salary. I wanted to continue learning,” she says. “I wanted to go to college and study English. I was denied the first time I tried.”

By the following year, she was the village’s only remaining former Beijing student. “When the college recruitment happened, again I applied to study foreign language. I was denied for the second time.”

Puzzled, she approached commune leaders for an explanation. They had dossiers on the sent-down students.

“They looked into my file and said, ‘Well, no wonder you were denied. Your father’s relative went to Taiwan when the Communists took over China.’ That deemed me not politically suitable to study foreign language. I thought, ‘It seems that’s the end of my dream to go to college.’ ”

By the end of her fifth year in exile, believing she might never attend college, she joined a teacher-training program in a nearby city. However, a budget crisis soon ended the program, and she returned to the village. A year later, she took the college entrance exams for the third time.

“A recruiter recognized the situation, my prior two times of rejection,” she says. “He said, ‘Why don’t you go to medical school?’ I said, ‘That’s not my interest.’ He said, ‘This will help you go to college, and studying Western medicine will require you to study foreign language.’ So I went to college.

“To be a doctor, it doesn’t matter whether you have relatives in Taiwan or not, according to the government standard.

“Because of all of those years of hardship … I don’t easily give up.”

After finishing medical school, Wang pursued a master’s of science degree in immunology at Beijing Medical University, graduating in 1981.

She wanted to come to the United States for her doctorate in immunology, because China had no doctoral programs at the time. She applied to a dozen American universities and was accepted by all. Cornell University offered a full scholarship. She and Huang married a few months before she left China.

“My medical school didn’t want me to leave,” Wang says. “After several months, they said, ‘Maybe you should get married and then you will be allowed to leave.’ I had to write a promissory note saying that my husband is remaining in China, and I’m going to the United States to do a Ph.D. and then afterwards I will return. But then he left, too.”

Huang was admitted to Tufts University to study American history and went on to Cornell for his doctorate in colonial American history. At long last, he had been reunited with his wife.

“My children keep telling me that I should write a book about my story,” Wang says. – Dixie Reid